19. January 2023

Franziska Krenz

It was the 2nd of January 2023 and the VAST FORWARD team was meeting for their weekly check-in via video call, as they do every Monday. It was the first working day of the new year.

We told each other about family visits and meetings with old friends, about delicious Christmas roasts, about appropriate and inappropriate gifts and about how we spent the turn of the year.

Most of us ate too much, some of us drank too much. Our children unwrapped far too many presents and perhaps a few of us had too much of their family at some point.

It wasn’t until I was talking to my colleagues when it struck me: I definitely streamed far too much in the time between the years.

And there we had it, one question and one mission:

The question: What impact did my “unrestrained” binge-watching have on the environment?

The mission: Write a blog post! About people’s streaming behaviour, how much we influence the climate with it and what we can do better in the future!

"Christmas is the glorious season of the great too much" Leigh Hunt, English author, 1784-1859

For almost three decades, streaming has accompanied our lives, growing steadily and helping us especially through the Christmas season, the New Year and the time in between.

Already in the days and weeks before Christmas, we wait for a contemplative mood to set in, which carries us beyond the Christmas season into the New Year. If this homely feeling doesn’t set in naturally, the immeasurable range of Christmas series and Christmas films in the video-on-demand program of numerous streaming providers can help. The Christmas playlists on Amazon Music Unlimited, Spotify, Apple Music and a wealth of other music streaming services reliably accompany us as we bake biscuits and crafting Advent wreaths.

And if we feel like it, on BibelTV`s live-church-services-platform we can attend the services of all Christian denominations of the channel’s partner churches.

At my house, a fireplace crackled via Netflix, while we unwrapped our Christmas gifts.

Although none of the people present unpacked a streaming subscription, this is no longer a rarity. Streaming subscriptions are increasingly common under the Christmas tree. Almost five per cent of consumers in Germany gave a subscription to a streaming service as a Christmas present in 2020. The year before, it was still around two per cent. This put streaming subscriptions in fifth place among the most popular Christmas gifts in 2020, which is certainly largely due to the Corona lockdown.

Last but not least, children and young people in particular used the well-deserved Christmas holidays for extensive YouTube and TikTok consumption. Insta-stories were posted and high scores in online games were cracked while video chatting with friends.

It is probably more due to the parents’ generation that the streaming of TV channels via the internet is also on the rise. In 2022, the share of German households that used TV access via their internet connection, i.e. received their TV programme via IPTV, was almost twelve percent.

And so, from year to year, the classics hits like “Three Hazelnuts for Cinderella” or “Dinner for One” are probably also floating into German living rooms more and more often via streaming.

Across generations, video calls with the family or video greetings to our loved ones add up on our streaming account, at the end of the year and especially at the turn of the year. An estimated 63% of Germans sent their New Year’s greetings via video calls on New Year’s Eve.

All in all, streaming currently accounts for about 82% of network traffic and is thus also the main source of digital pollution.

The number of streaming services is constantly increasing, as is the number of users. With this rapid growth, the environmental impact is also increasing.

In 2025, streaming will be 30 years old.

According to the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), it is likely that by then we will also already exceed the 1.5-degree global warming limit, although not permanently for the time being.

According to a study published by the French “The Shift Project” in 2019, half an hour of streaming is said to cause 1.6 kilograms of carbon dioxide, which is equivalent to driving 6.2 kilometres.

Although the Fraunhofer Institute has disproved the accuracy of this calculation, streaming still causes a share of climate-damaging greenhouse gases that should not be underestimated.

The commercial use of the internet began in 1990.

At that time, the World Wide Web offered rather rudimentary possibilities for use and was hardly fun for non-professionals. Users connected to the internet via the low-capacity lines of the existing telephone network. Basically, only the reading of data-light texts was possible.

In 1993, the NCSA Mosaic web browser was one of the first to display still images on the browser page. In the same year, the Internet was estimated to account for only 1% of the information flows of the world’s telecommunication networks.

In order for sounds and videos to be distributed over the telephone lines available at the time, the data first had to be converted to a digital format and then heavily compressed.

This was also helped by a German invention that officially received its name on 14 July 1995 – mp3.

Karlheinz Brandenburg and his team at the Fraunhofer Institute for Digital Media Technology (IDMT) worked for almost 10 years to slim down an audio file so that only the information that was important and pleasant for the brain remained and can thus be transmitted over telephone lines. For his studies, he chose the acapella version of the song “Tom’s Diner” by Suzanne Vega, which was popular among experts at the time for testing loudspeakers.

Shortly after the introduction of mp3, another milestone on the road to streaming followed. Perhaps the 5th of September 1995 can even be called the birth hour of internet streaming.

On that day, RealNetworks put the first live audio stream on the internet, a commentary on a baseball match between the Seattle Mariners and the New York Yankees.

Two years later, in October 1997, the first streaming video went online – a short film by Spike Lee, produced especially for the launch of RealPlayer.

The start of video streaming was rather bumpy, because here, too, the files first had to be slimmed down. The problem: a video needs data-intensive details to be displayed smoothly – compression means omitting precisely these. Downsampling the number of pixels in the image meant a loss of data and resulted in rather poor picture quality.

In the 1990s, the content and quality of audio and video streams still had to bow to the infrastructure, but with the growing internet use and the introduction of new technologies, compression soon became useless and fell away.

The beginning of this development is probably the introduction of ADSL in the early 2000s.

The broadband network enabled higher speeds and a greater flood of data than the telephone network used until then – broadband freed the world from the shackles of compression. However, while ADSL was fast and powerful in its early days, it was also unstable. Since data is read in real time when streaming, the broadband network in its early days tended to spoil the fun of streaming with jerky playback.

The first attempts at streaming were rather bumpy. So it’s no surprise that the download boom preceded streaming. Back then, downloads took a long time because the entire file had to be transferred to the computer first. But as soon as it was completely downloaded, it could be played back smoothly with one click.

And although a download took a long time, it opened up a whole new world to us: The limitless supply.

On top of that, the flood of data was mostly free because it was illegal. Computers overflowed with music and films, servers overheated and power consumption soared.

The older ones among us will still remember how our computers ran for nights on end due to the limited download speeds and unbridled consumption of films and music.

In addition, not least due to downloading itself, the number of computers and internet connections in German households increased by leaps and bounds.

Whereas in 1998 just under 39% owned a computer and 8% had an internet connection, five years later 61% already owned a computer and 46% were connected to the internet.

Another 20 years later there is hardly any room for improvement – today 92% of German households have at least one computer and 95.5% of households call an internet connection their own.

A devastating development for the environment that hardly anyone noticed.

Originally to protect copyright, record companies took refuge in streaming and thus ended the download flood. In fact, in the end, streaming prevailed over downloading – also thanks to small monthly subscription costs.

However, with the advent of streaming subscriptions, a new problem entered the world: users no longer physically own the data, but it is sent through the pipes anew every time a song, a video, a film, a series is played, causing climate-damaging emissions, over and over again.

On 24th April 2005, the first video was put online on YouTube. At this point, streaming became mainstream, because now every person who had access to a computer and an internet connection had the opportunity to put their own videos on the web. It is hard to believe today that not so long ago this was not possible.

In the meantime, almost 6 billion videos are consumed on Youtube every day – that`s 4 million videos per minute.

The first iPhone was presented on the 9th of January 2007 and was launched on the German market at the end of the same year. This innovation – “an iPod, a phone and an internet communicator in one device” – and the introduction of the new mobile phone standard 4G, two years later, finally ensured that we can carry the internet around with us all the time and thus stream whenever and wherever we want. And that’s what we do.

The pollution caused by streaming is mainly based on psychology: the impact of streaming on the environment was and is not visible to us.

Around 2010, terms like “virtual” and “cloud” began to appear. They convey the image of an imaginary and pure white cloud, obscuring the fact that the internet is actually made of cables and computers interspersed with metals and plastics, and data that travels through data centres where it consumes vast amounts of energy.

So a clever marketing move has dematerialised streaming and distorted the perception of its users. Who cares that the cloud is not really a cloud and that data does not just float through the air.

In fact, the immaterial pollutes the environment more than the material.

In 2020, the music streaming service Spotify caused about 169,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions. That is more than the entire US record industry caused in 2000 – back when music was primarily pressed on compact disc.

Given the rapid development of streaming, it is high time for us to rethink our actions.

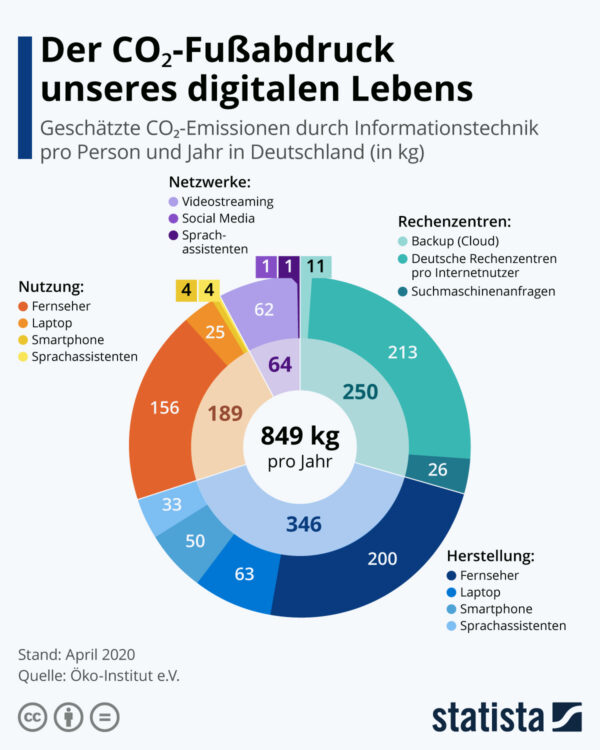

Every single one of us leaves a CO2 footprint of around 849 kg in our digital lives.

Streaming takes up a not inconsiderable part of this – through the use of data centres, network infrastructure and digital devices.

Whether it’s a video, film, song, podcast episode, TV programme or webcam image – everything we stream every day feeds these three sources of greenhouse gas emissions, which we’ll be taking a closer look at in the next episodes of our streaming series.

Sources:

Sustainability of Streaming by bitkom.org (DE)

Video-Streaming and CO2 by bitkom.org (DE)

digital campfire by bitkom.org (DE)

Streaming behaviour of the Germans by marktforschung.de (DE)

Virtual Christmas by videoaktiv.de (DE)

Frankenstream by arte.tv (EN)

History of the Internet by wikipedia.org (DE)

20 years of mp3 by t-online.de (DE)